Identity, Morals, and Taboos: Beliefs as Assets

The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(2), 805–855.

Table of Contents

- Background

- Identity, Morals, and Taboos

- Motivating Facts And Puzzles

- Solution: Belief as Assets

- The Model

- Benchmark Cases

- Equilibrium and Welfare: Solving the model

- Taboos and Transgressions

- Conclusion and Discussion

Identity, Morals, and Taboos: Beliefs as Assets

The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(2), 805–855.

Table of Contents

- Background

- Identity, Morals, and Taboos

- Motivating Facts And Puzzles

- Solution: Belief as Assets

- The Model

- Benchmark Cases

- Equilibrium and Welfare: Solving the model

- Taboos and Transgressions

- Conclusion and Discussion

Background

Jean Tirole

- Nobel Prize (2014)

- Honorary Chairman, Toulouse School of Economics (2019)

- Ph.D., MIT (1981)

Research interests

Industrial Organization, Regulation, Organization Theory, Game Theory, Finance, Macroeconomics, Psychology

Roland J. M. Bénabou

- Jean-Jacques Laffont Prize (2021)

Lecture "Beliefs and Misbeliefs: The Economics of Wishful Thinking" - Professor at Princeton University (1999-)

- Ph.D., MIT (1981)

Research interests

inequality, growth, social mobility and the political economy of redistribution; education, social interactions and the socioeconomic structure of cities; economics and psychology ("behavioral economics")

Economics "invade" Psychology

Provide an economic view

This paper provides a extremely flexible and feasible model to explain experimental results from Behavioral Economics and Psychology.

Strength of the model but…

Identity, Morals, and Taboos

Three things cannot be explained by standard model

Identity

- "Who I am"

- Experimental evidence: People care about Identity

- People with a strong identity(willpower) can resist the temptation and self-control

Morals

- "Am I a moral person?", based on your own decision

- Experimental evidence: People reject the deceptive but profitable choice(Gneezy, 2005)

- People’s economic decision is constrained by Moral Concern

How to explain these results?

- In former models:

- include social preference assumptions

- People’s utility = Economic utility + Social Utility

- e.g. cheating helps to get higher grades, but I still wanna be a honest student because keeping honesty brings happiness

- It is called "second generation of moral behavior"

Taboos: Information-Averting Behaviors

- People think it "immoral" to place a monetary value on some "priceless" concepts

- People prohibit themselves from merely thinking about taboos

- e.g. Markets for organs, genes, sex, surrogate pregnancy andadoption are widely banned on grounds that they would represent an “unacceptable commodification” of human life

- "More information is not better" under some situations

Motivating Facts And Puzzles

Unstable Altruism

Positive Side:

People have strong preference for being a good person.

- fairness, cooperation, and honesty in social interactions(anonymous, one-shot)

Negative Side:

People prefer to act selfishly to gain extra money while "feeling moral".

- Excuse-seeking behavior(e.g. Garcia et al., 2020)

- "I do not want to donate money because charities are not reliable "

- Moral Wiggle Room (e.g. Dana et al., 2007)

- when a decision is uncertain in morality, people tend to strategically behave selfishly

Coexistence Of Social And Antisocial Punishments

Social Punishments

- free-riders in public-good games, and violators of social norms more generally, get punished by others

Antisocial Punishments

- who behave too well elicit resentment, derogation, and punishment from their peers

- Such do-gooders always exhibit stronger moral principles or resilience than their peers

Solution: Belief as Assets

Third-generation theory of Moral Behavior

- Belief as Assets

- let moral identity as beliefs about one’s deep “values”

- holding a positive self-image can increase utility

- Self-inference Process

- judge oneself by own behavior or decisions

- "Who Am I" partially comes from inference based on former decisions

- How can self-inference happen

- use imperfect memory or awareness

- because sometimes we are not sure "How good I am", we use self-inference

- The result of self-inference

- investment for identity management

- choose the decision to let the self-inference process produce the positive belief

The Model

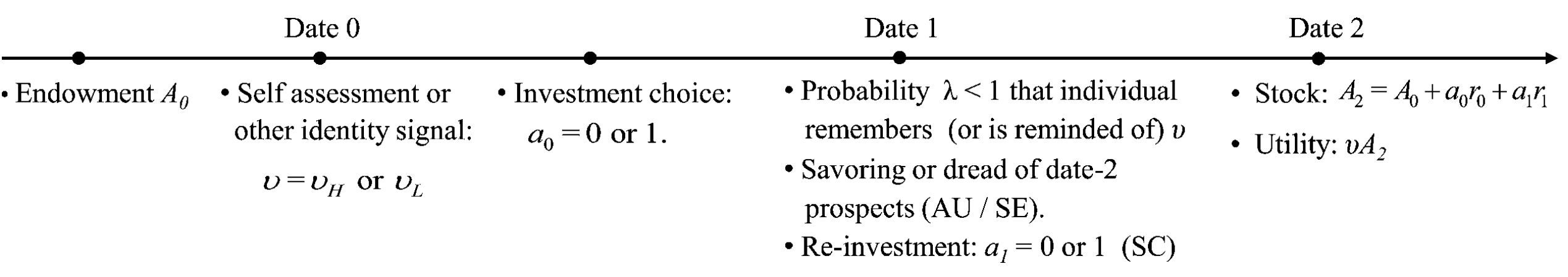

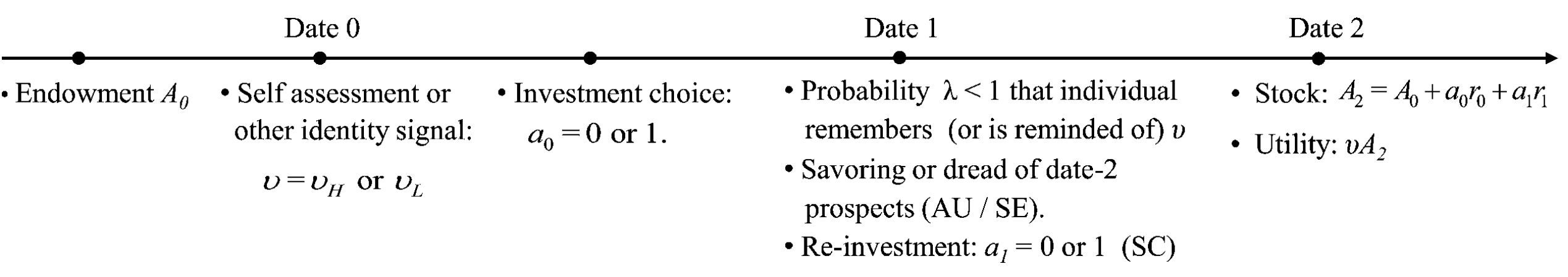

Timing of Moves and Actions

Notations

A are “relational assets” and the individual’s long-run utility

v is person’s type "good or not"

at is investment decision. (= 1 invest in A, and = 0 not)

rt: the multiplier of moral decision

At+1=At+αtrt to measure the relative increase from choosing at=1

Date 0. self-assessment → v

the agent has access to a signal about his type(good or bad)

v={vHvL with probability ρ with probability 1−ρ

prior expectation:

vˉ≡ρvH+(1−ρ)vL

Assumption 1

The net cost of investment at date 0 is c0H≷0 for type H and c0L for type L, with c0L≥c0H

Because a more prosocial individual internalizes more of the benefits accruing to other people, even in one-shot interactions, he finds it (weakly) less costly to act morally—help, refrain from opportunism

Date 1. Self-Inference → v^

Assumption 2. (Self-inference)

the individual is aware of his true valuation v only with probability λ, so with (1−λ), he cannot remember and infer his type based on former choice a0

denote ρ^ as date-1 belief about his type

v^≡ρ^vH+(1−ρ^)vL

so with probability λ, v^ is v; and with 1−λ, v^=v^(a0)∈[vL,vH]

Note:

(1−λ) is malleability of beliefs, the probability of information loss thus also reflecting the possibility that deeds may themselves be forgotten or repressed, or be uninformative due to situational factors that can be invoked as plausible excuses

Date 1. Self-Inference → v^

Assumption 3

The value function V=V(v,v^,A1) satisfies Vv^>0, Vv^v≥0 and, if r0>0, VvA1>0.

Vv^>0: a “good identity” convention, a moral self-image is better than not

Vv^v≥0: a sorting condition, when c0H≤c0L , the investment of H type ≥ the investment of L type (behaving more prosocially), so that actions have informational content(type can be identified from the action)

Assumption 4. Exclude the Trivial Case

we do not want: the investment cost is too low so that both types always invest regardless of identity concerns

we assume:

V(vL,v^=vL,A0+a0r0)−V(vL,v^=vL,A0)<c0L

Date 2. Future

vA2 is long-term value

Benchmark Cases

- We use two benchmark cases to get more interesting results

- Each case has a specific V(v,v^,At) function

reminder of our timing:

Benchmark Cases

Case 1: Anticipatory Utility(self-esteem)

Decision only happens at Date-0

a1≡0,A2=A1

What is AU: hopefulness, anxiety, or dread that arise from contemplating future and social prospects

Long-term Utility

vA2, the expected value of social relationships(family, friends, colleagues, ethnic group, etc.)

Intertemporary utility function

V(v,v^,A1)=sv^A1+δvA2

s: anticipatory feelings or salience

δ: the time discount factor

Self-esteem is a special case of anticipatory utility

SE is AU when At≡1,rt≡0 and δ=0, so

V(v,v^,A1)=sv^A1+δvA1=sv^

Welfare Analysis

total intertemporal utility

W≡E[−a0c0+V]

depends on:

- prior beliefs v∈{vH,vL}, which depends on ρ

- posterior beliefs v^∈{v,v^(a0)}, which depends on λ

Case 2: Self-Control

Present bias

At date 1, a myopic person’ perceived cost of acting morally is c/β(β<vL/vH)

so β exaggerate present cost c

Investment decision a0 happens when t=0,1

- Investment at t=1 involves a stochastic cost c1

- type-independent distribution F(c1) on R+

Case 2: Self-Control (Cont.)

Moral Identity and Self-Restraint

given a self-view v^, the agent invests when c1/β≤δv^r1, so threshold cost increases with v^

Total Intertemporal Utility

V(v,v^,A1)≡δvA1+∫0βδv^r1(δvr1−c1)dF(c1)

δvA1: default long-run utility

(δvr1−c1): extra utility from investment choice

Welfare Analysis

W=E[−βa0c0+V]

β is reversed present bias from Date-0

Equilibrium and Welfare: Solving the model

Utility Maximization

Expected Value Function

V(v,v^,A1)≡λV(v,v,A1)+(1−λ)V(v,v^,A1)

Each type chooses his optimal option a0, k=H,L

a0∈{0,1}max{−c0ka0+λV(vk,vk,A0+a0r0)+(1−λ)V(vk,v^(a0),A0+a0r0)}

Utility depends on v^(a0) and a0

v^(a0)≡ρ^(a0)vH+[1−ρ^(a0)]vL

where ρ^ relates to ρ,xK

ρ^(1)=ρxH+(1−ρ)xLρxH , ρ^(0)=ρ(1−xH)+(1−ρ)(1−xL)ρ(1−xH)

xH and xL: probabilities that types H and L behave prosocially at t=0

Utility Maximization (Cont.)

Investment choice (a0=1) is optimal when:

V(vk,v^(1),A0+r0)−V(vk,v^(0),A0)−c0k≥0,k=H,L

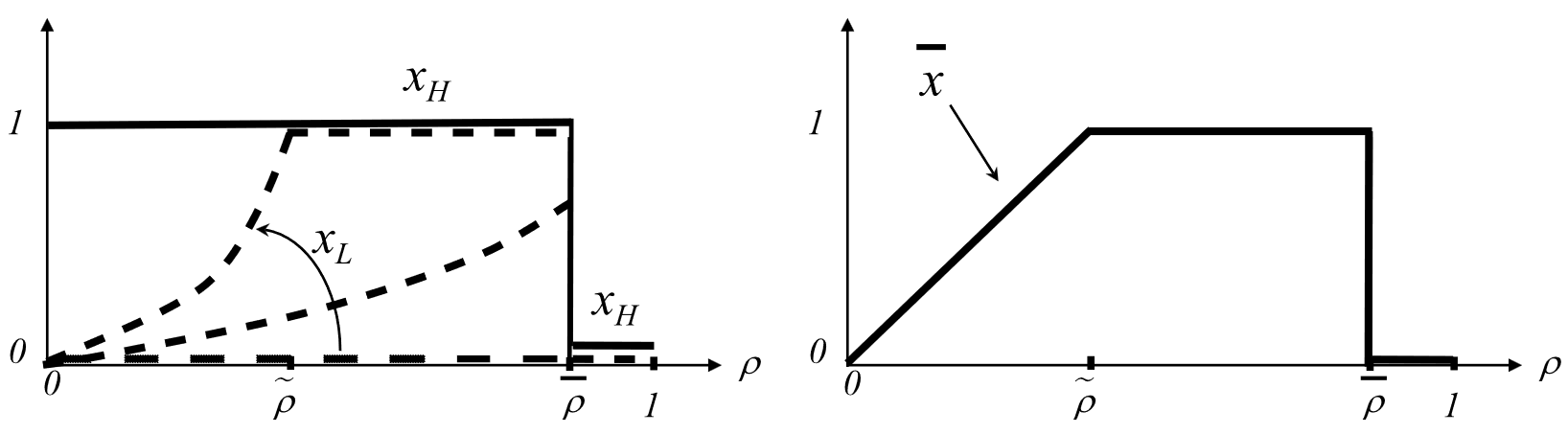

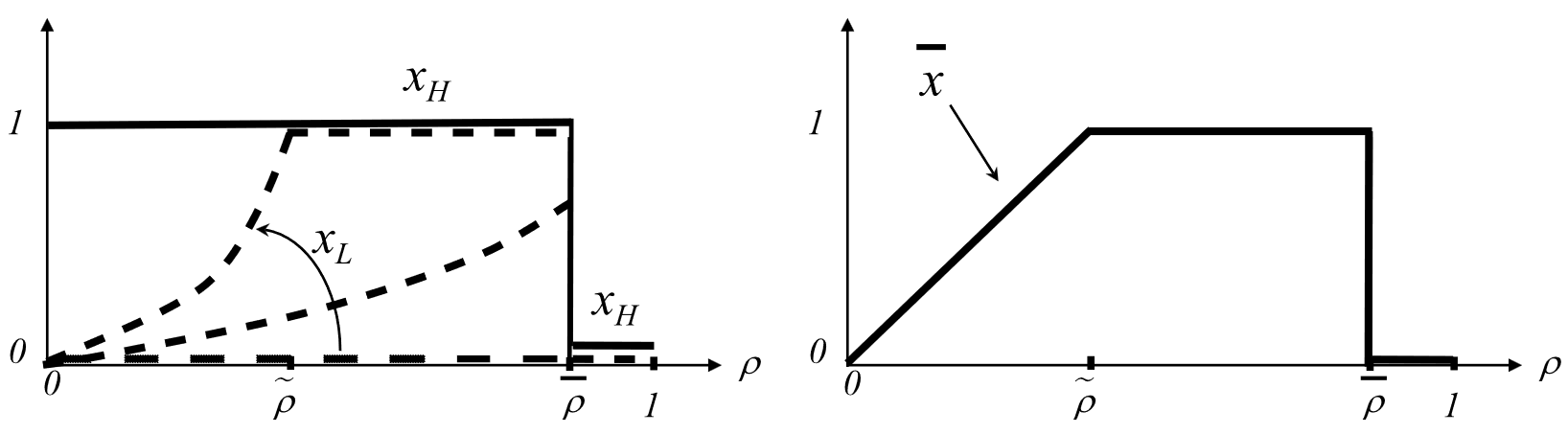

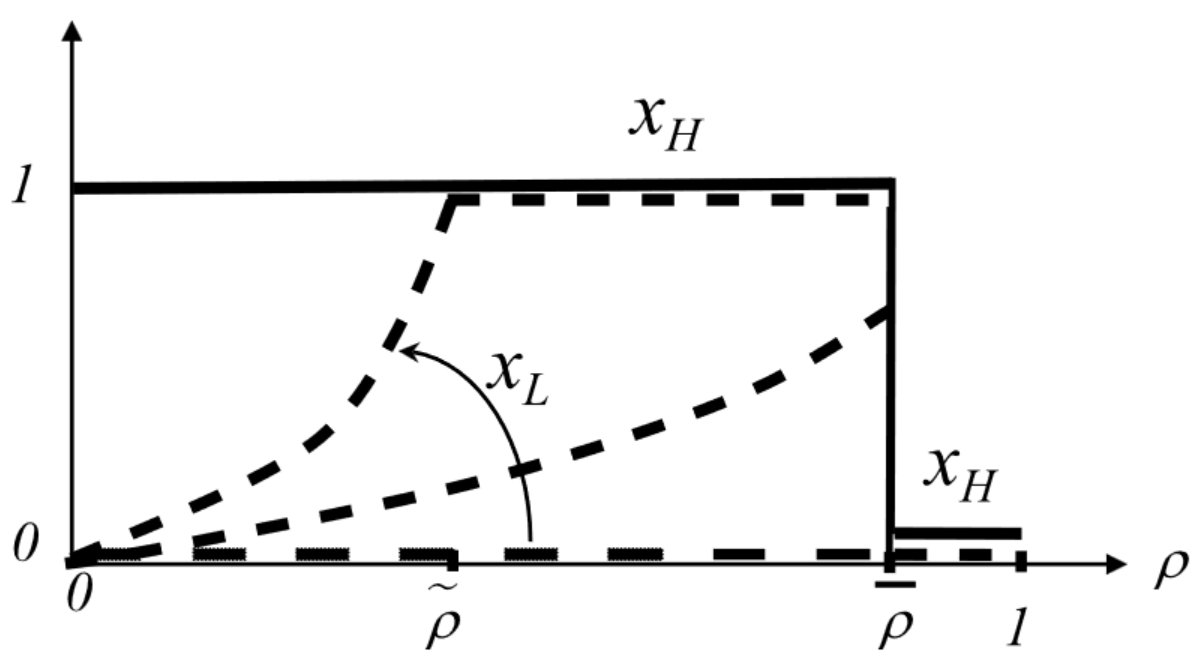

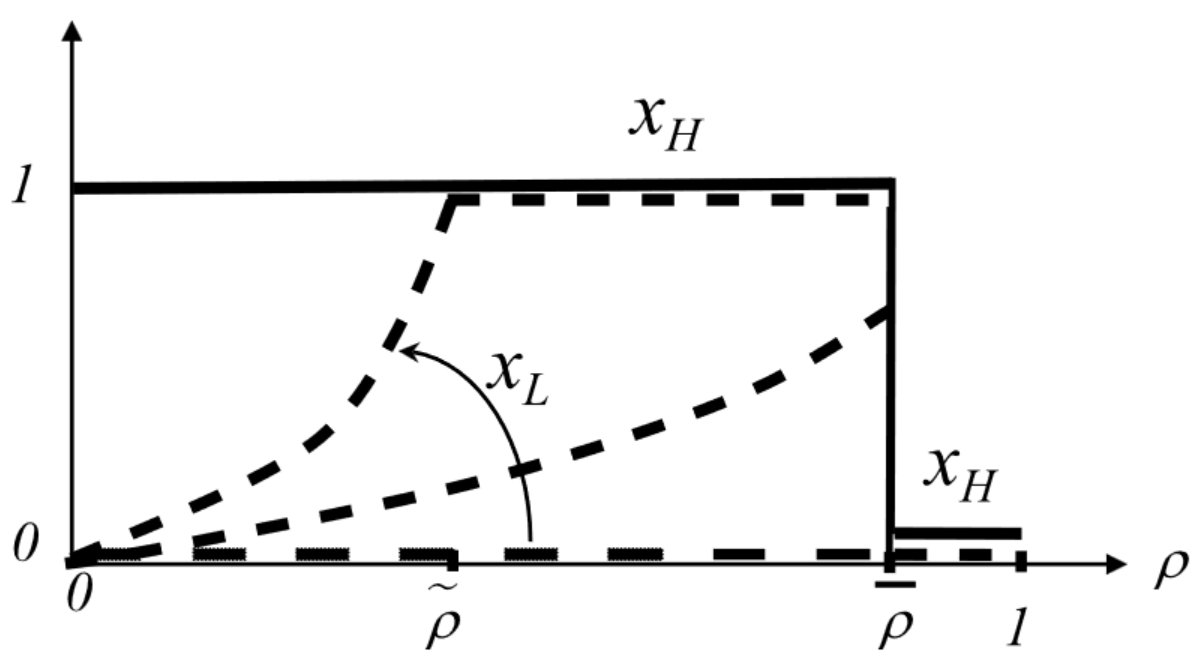

Monotonic Perfect Bayesian Equilibria (Proposition 1.)

- xH(ρ)=1 for ρ<ρˉ and xH(ρ)=0 for ρ>ρˉ

- xL(ρ) is non-decreasing on [0,ρ~] ,equal to 1 on [ρ~,ρˉ) when ρ~<ρˉ and equal to 0 on [ρˉ,1]

No Investment. (ρ>ρˉ)

ρ = initial self-image inference

When initial self-image is good enough, the H type can afford not to invest, since the other one also behaves opportunistically the posterior will equal the prior, which is already close to 1 and thus could not be increased much anyway

Investment Cases. (ρ<ρˉ)

H invest to “stand for his principles” and separate from the L type

Separation.

When c0L is high, the low-valuation type does not find it worthwhile to invest (xL=0)Randomization.

For lower values of c0L, L type intend to imitate H type (but ability of imitation is limited by the prior)Universal Investment.

For c0L still lower, even a small gain in self-image is worth pursuing, so xL=1.

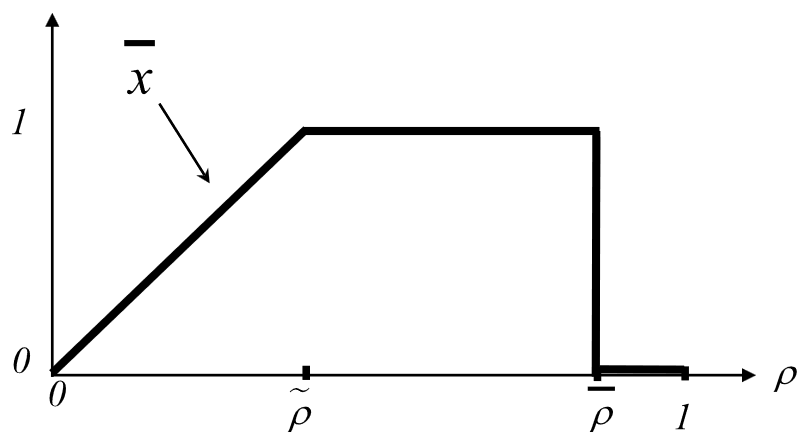

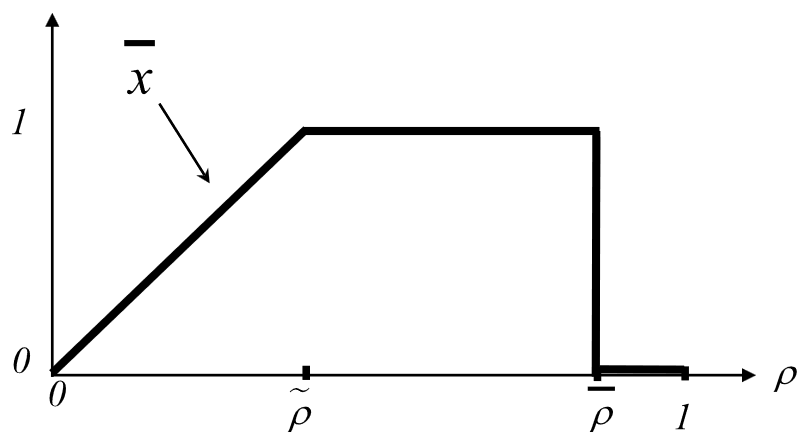

Comparative-Statics Analysis (Proposition 2.)

- An individual invests more in identity if

- more malleable self-belief(λ↓)

- lower investment cost (c0L↓ or c0H↓)

- more salience (SE/AU case, s↑)

- higher the capital stock A0(AU case, A0↑)

- Initial beliefs have a non-monotonic, hill-shaped effect on overall investment

Treadmill Effect (AU/SE case)

Let’s examine the no-investment condition:

V(vH,vH,A0+r0)−V(vH,vˉ,A0)=(s+δ)vHr0+(1−λ)s(vH−vˉ)A0≤c0H

Notice that when A gets sufficiently large, the agent unavoidably chooses to invest, thus reducing his/her lifetime utility.

More broadly speaking (easy to see when r0≈0):

W=ρxH[(s+δ)vHr0−c0H]+(1−ρ)xL[(s+δ)vLr0−c0L]+(s+δ)vˉA0.

The first two terms decrease as identity investment rises.This leads to more interesting findings.

Proposition 3.

In Anticipatory Utility case:

- An increase in the malleability of beliefs (1−λ) always reduces welfare.

- An increase in capital A0 can make the individual worse off.

- An increase in salience s can lower welfare

reminder: when r0 is relatively small, the underlined items are negative

W=ρxH[(s+δ)vHr0−c0H]+(1−ρ)xL[(s+δ)vLr0−c0L]+(s+δ)vˉA0.

Commitment Value of Identity (Self-control case)

let assume two cases:

(a) λ=1, neither type behaves prosocially at t = 0 : c0H>δvHr0, so xH=xL=0

(b) λ<1, the equilibrium involves mixing: H type cooperates, while L type randomizes.

Difference in intertemporal welfare:

ΔW=W(b)−W(a)=(1−ρ)xL(δvLr0−βc0L)+ρ(δvHr0−βc0H)+(1−λ)E[ΔV]

where E[ΔV] reflects the effects of self-image management on date-1 behavior:

E[ΔV]=(1−ρ)xL∫βδvLr1βδv^(1)r1(δvLr1−c1)dF(c1)−ρ∫βδv^(1)r1βδvHr1(δvHr1−c1)dF(c1)

Proposition 4.

In the self-control case, more malleable beliefs (λ↓) can raise welfare, by improving choices at t=1 (when E[ΔV]>0) and/or at t=0 when ΔW>(1−λ)E[ΔV])

Taboos and Transgressions

Taboos and Transgressions

- self enforced, aims to avoid dangerous (self-) knowledge that might surface from “cold” analytical contemplation of what short-run tradeoffs might be available or expedient

- socially enforced, is a form of information destruction aimed at repairing the damage to beliefs caused when someone, through his actions or speech, has violated a norm or taboo.

Self-enforced Taboos

Setting:

type(v)

Let v∈vH,vL denote the long-run value of some important asset, relative to At

Taboo breaking = Selling decision of Assets

Suppose date=0, an agent can find a price p and sell one unit of A0

price distribution is:

p={pH with probability zpL with probability 1-z

Investment choice (a0)

choice={a0=0,check the price + consider selling A0a0=1,keep the taboo, think it priceless

💡 contemplation is done once check

the agent will recall that he contemplated the possibility of a transaction and evaluated whether maintaining his identity or dignity was “worth it”

Selling decision depends on price found

let pH be high enough and pL low enough → transact or not is a signal of type

when p=pH: always sell A0, implies: when p=pL: no transaction, implies:

pH>V(vH,vH,A0)−V(vH,vL,A0−1)pL<V(vL,vH,A0)−V(vL,vL,A0−1)

Taboo holding Condition (in AU and SC case)

V(a0=1)−V(a0=0)=V(v,v^(1),A0)−V(v,v^(0),A0−z)≥zpH+(1−z)pL≈zpH

A special case of former modelwhere a0r0=z,c0=zpH and initial stock A0′≡A0−z

Note.

V(v,v^(0),A0−z) can be written because V is linear in A1 in AU and SC case

Conclusions

How taboos arise and are sustained

from proposition 1 and 2, it depends on the initial beliefs ρ

- Full-investment equilibrium

- More committed (mixing or separating equilibrium)

Conclusions (Cont.)

Taboo’s Reaffirmation or Collapse

according to which side of the “hill” the induced erosion of ρ occurs on

on the right side

ρ decrease → reaffirmationon the left side

ρ decrease → collapse

Conclusions (Cont.)

Welfare effect of taboos

- In AU case: upholding taboos generally lowers an individual’s ex-ante welfare

- In Self-control case: it can be beneficial, but only under specific conditions

Note.

Proposition 3. An increase in (per se valuable) capital A0 can make the individual worse off.

Socially-enforced taboos

Focus: coexistence of social and antisocial punishments

New elements

- Investment Choice (a0)

- a0=1: with probability θ, the decision is not socially beneficial; with probability 1−θ, a0=1 is socially beneficial, return of relational capital is

r0k=ξvk,c~0H≥c~0L

ξ=1 when the action benefit others and ξ≤0 when not

New elements (Cont.)

- Ostracism Decision (yi)

continue relationship or not: two agents after observing each other’s action, decide whether to continue in the relationship (yi=0) or to break it (yi=1)

interactions benefit: if someone exit, both lose b

- Agent i utility function

(viξ−c0i)a0i+V(vi,vi,A0+r0a0i)+(1−ν)(1−y)b

ostracism happens condition: y≡1−(1−yi)(1−yj)

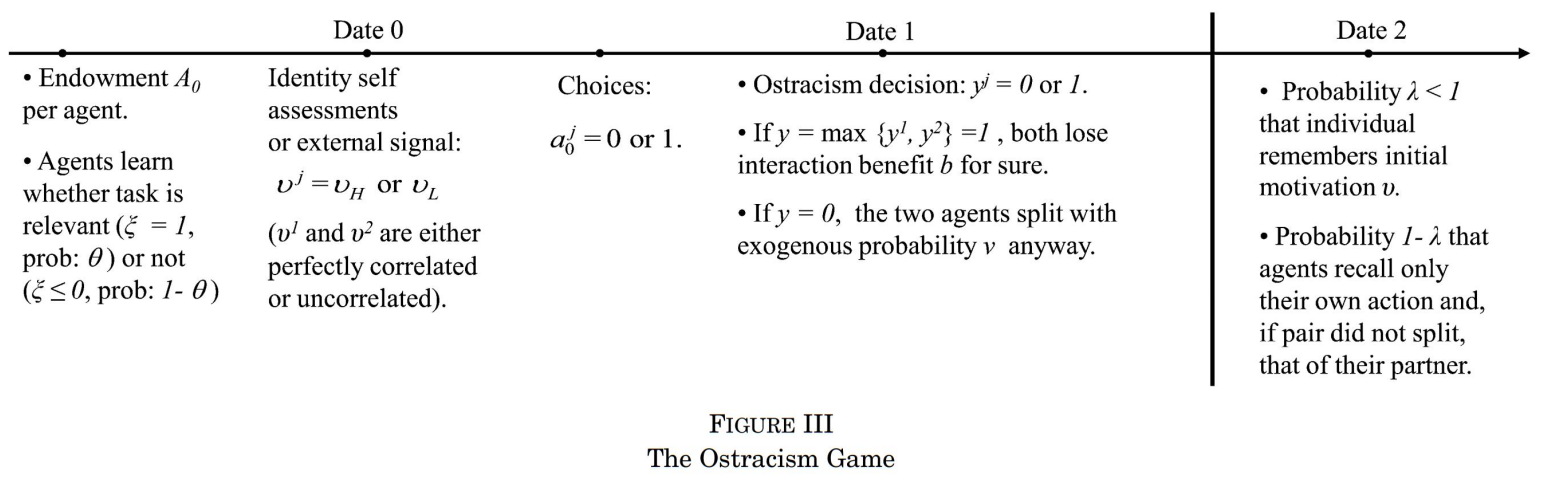

New Timing

Date 1: (no-recall assumptions) each agent always remains aware of his own behavior ai0, but he recalls that of his partner only if they are still together. If a split occurred, he recalls neither a0j nor what caused the separation (extreme and meant only to simplify the derivations)

Two Extreme Benchmark

1. Benchmarking on the Person

two types are the same v1=v2∈{vH,vL}

a0 is always socially useful (ξ≡1)

2. Benchmarking on the Situation

two types are independent

Whether a0 is socially useful is random: ξ=1, with probability θ or ξ≤0, with 1−θ

When faced with a given situation agents are able to assess ξ, but later on they recall imperfectly with probability 1−λ.

Proposition 5.

In an equilibrium such that the H type invests when (ξ=1), let x∈[0,1] denote the probability of investment by the L type.

Ostracism occurs only when actions differ, i.e. one agent invests and the other not.

- because each agent has an incentive to exclude those who act differently from him

- social conformity arises endogenously from self-image concern

Co-existence of Social punishment and Anti-social punishment

benchmarking is on the person = Social punishment

ostracism comes from the good agent

benchmarking is on the situation = Anti-social punishment

ostracism comes from the bad agent

Proposition 5 (Cont.)

- With both the AU/SE and SC specifications and under either type of benchmarking, there exists a (positive-measure) range of parameters such that both x=1 and x=0 are equilibria:

When benchmarking is on the person

x = 1 is sustained by the ostracism of “sinners” (a prosocial norm)

x = 0 involves no ostracismWhen benchmarking is on the situation

x = 0 is sustained by the ostracism of “do-gooders” (an antisocial norm)

x = 1 involves no ostracism

shows cross-society-differences in civic norms and how they are enforced

Conclusion and Discussion

Conclusion

- A more general third-generation theory of moral behavior, individual and collective, based on the identity in which people care about “who they are” and infer their own values from past choices.

- The paper proposed the monotonic Perfect Bayesian equilibria of welfare with three scenarios.

- Taboos can be formed by internally enforced and socially enforced

- High endowments trigger escalating commitment and a treadmill effect

- Competing identities can cause dysfunctional capital destruction

Further Applications

Other Dimensions of Identity

- Salience of Identity

Messages or cues that make specific components of a person’s identity more salient elicit investments along the same dimensions.

Application of salience is advertising, much of which plays up people’s desires to achieve or affirm certain identities—raising s with respect to beauty, wealth, or social status. Proposition 3 shows that such messages can be very effective in inducing consumers to purchase ( a0=1) and yet substantially lower overall welfare.

Proposition 3. In the anticipatory utility or self-image case:

- An increase in the malleability of beliefs (1−λ) always reduces welfare.

- An increase in (per se valuable) capital A0 can make the individual worse off.

- An increase in salience s can also lower welfare

- Uncertain Values and Malleability of Beliefs

People are insecure about “who they are” (ρ in the middle range) are the most prone to costly identity-affirming behaviors. E.g. adolescents; male subjects with strongly declared homophobia actually showed the most arousal in response to male homoerotic videos.

- Escalating Commitment

someone who has built up enough of some economic or social asset—wealth, career, family, culture, etc.—continues to invest in it even when the marginal return no longer justifies it. This leads to excessive specialization (e.g., work versus family) and persistence in unproductive tasks

e.g. A manager will thus keep throwing good money after bad on a doomed project

Extensions of the Basic Model

Social Signaling. In addition to their self-image v^, people also care about others’ perceptions v^′ of their type, resulting in a continuation value of the form V(v,v^,A1,v^′) Since others make inferences from observed behavior, adding a social signaling concern is akin to amplifying the self-image motive, so the entire analysis carries over (see again Appendix II).

The expected value function playing the role of Equation (11) is now

V(v,v^,A1)≡λV(v,v,A1,v^′)+(1−λ)V(v,v^,A1,v^′)

Thus, as long as

(v,v^,A1)⟼V(v,v^,A1,v^′)

satisfies Assumption 3, adding a social signaling concern is akin to amplifying the self-signaling motive (from

(1−λ)V2to(1−λ)V2+V4

and the whole analysis, positive and normative, carries over.

Competing Identities and Dysfunctional Behavior

Tradeoff between the future benefits from two identities, investing in one (say, B) inevitably damages the other (A), as it suggests that the individual may not value it that much.

- Resistance to Structural Change

The transition, which is risky and requires new skills and lifestyles, will be resisted if it is seen as de-valuing the old (rural, extended-family, blue-collar, etc.) identity

- Resistance to Assimilation

Immigrants and their descendents experience strong tensions between integrating into Western societies and preserving their specific culture.

- Destructive Identity, Discrimination, and Communitarianism

Not investing in B in order to safeguard beliefs about the value of A can also mean actively destroying productive B capital. E.g young rioters attacked and destroyed a number of schools, nursery schools and cars in their own communities.

Conclusion

- A more general third-generation theory of moral behavior, individual and collective, based on the identity in which people care about “who they are” and infer their own values from past choices.

- The paper proposed the monotonic Perfect Bayesian equilibria of welfare with three scenarios.

- Taboos can be formed by internally enforced and socially enforced??

- High endowments trigger escalating commitment and a treadmill effect

- Competing identities can cause dysfunctional capital destruction

Questions

- How would you modify this model to incorporate depression and low self-esteem? Would you expect depression to be associated with greater or lower a? Explain why. Is it consistent with the behavior of Mother Theresa, who suffered from severe depression?

V=(v^+sδv)A,

Answer. When a person is low in self-esteem, they will not gain not much utility from a higher type, which reveals that s is low. As a result, a low-esteem person will lay more emphasis on self-inferred utitlity, so they may do some extreme or srtange things to strengthen their identity pereption.

Questions

- As people age and gain experience, presumably λ increases. However, it is not obvious that young adults are less pro-social than older adults; on the contrary, they may be more earnest and sanctimonious than their elders, who may share the decidedly un-Calvinist sentiments of Cal Smith. What other factors are likely age-related and, ultimately, would you expect a to rise or fall with age?

Answer. Actually, we have experimental evidence shows that deceptive behavior significantly decreases with age (Glätzle-Rützler & Lergetporer, 2015), and another paper studying on the same relationship not got the significant results, but their adopted experimental paradigm may not ensure the credibility of individual-level data (Bucciol & Piovesan, 2011).

Aging changes people’s enjoyment from social capital - gaining a bossom friend at your twentieth is different from knowing awesome friend when you are at the end of your life.